Why There May Be Lots More Writing for You After Your Book Is Edited

One thing that surprises new authors when working with an editor is how much work they still may have to do after an edit. There are several reasons this happens

2017 Year in Review and Expectations for 2018

I launched into uncharted waters in 2017, propelled by an exponential influx of work I did not foresee. It was so much that I was forced to make a choice--keep my day job or follow the demand. I chose to follow the demand...

Not Clearly Establishing a Target Audience Will Ruin Your Writing

One mistake I see authors consistently make is trying to make their book relate to everyone. You cannot write for everyone. Choose a target and hit it on the bulls'-eye. Let the residual or secondary audience present itself organically.

Officially Unbossed

After fourteen years as an in-house book publishing editor, I have officially broken free from the corporate matrix. That’s right: you are looking at a free agent.

Your Book Is a Business

Each book is like its own business unit. The book proposal is like a business plan. Publishers are your investors. Readers are your customers and end users. How do you think an investor would look at a business if it hadn't thought about its competition and the market it is seeking to enter?

FAQ: Who Do I Need on My Independent Publishing Dream Team?

If want to publish an industry-competitive book without the industry restrictions, here are the independent publishing professionals you’ll need on your team to pull it off.

FAQ: How Long Will It Take for My Book to Be Written or Edited?

Having worked in traditional publishing for fourteen years and serving as editor, writer, and employer of freelancers that perform similar services, I have calculated the following ranges of time for how long it may take to ghostwrite or edit your book.

Invisible Chameleon: Secrets to Keeping My Voice Off an Author’s Words

Ghostwriting is definitely all about the author and the way they want to present a topic. An aspiring ghostwriter and author asked me about this process. Here's what I told them about how I try to keep the author's message front and center.

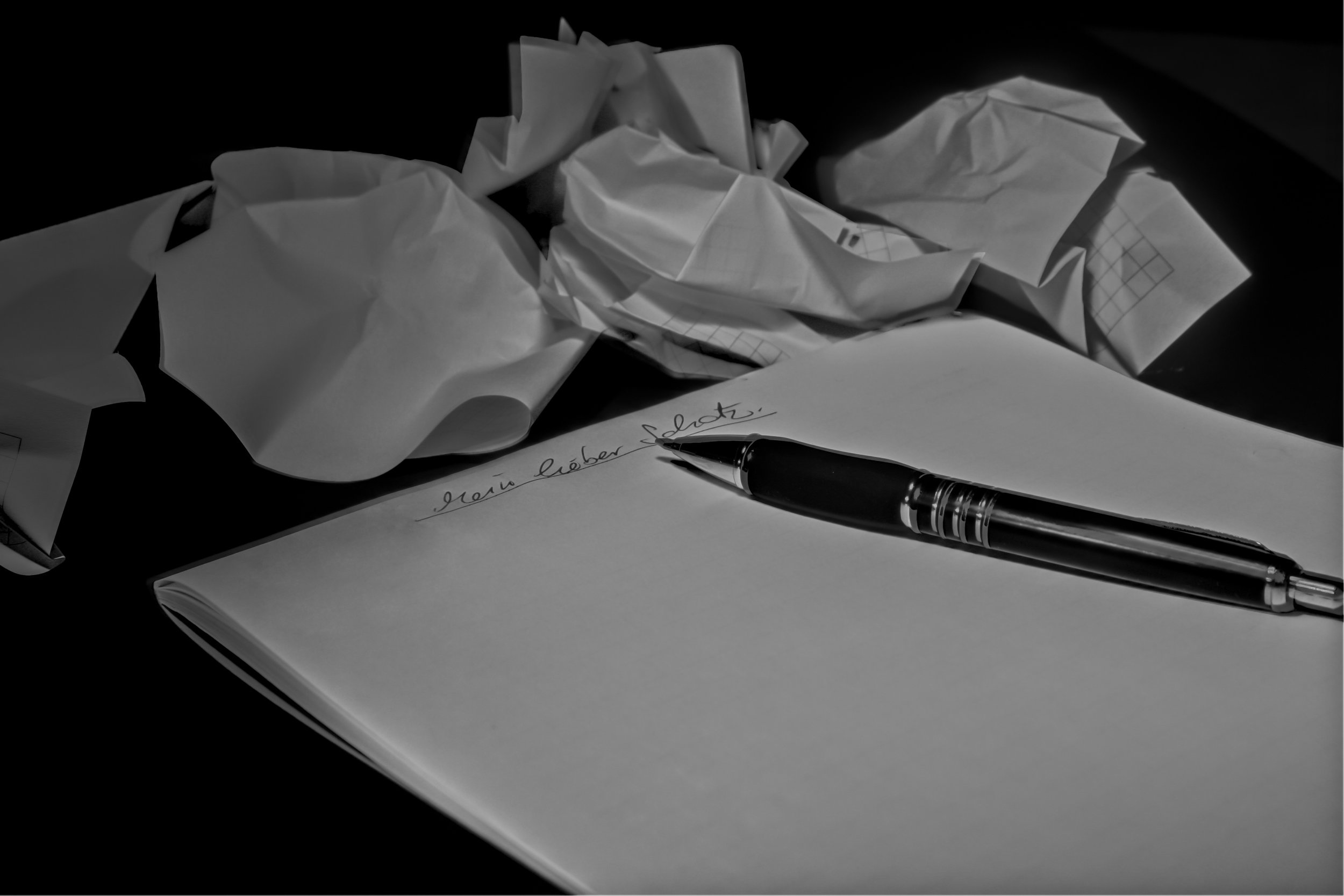

Approve Yourself. Accept Your Own Manuscript. And Call It Done.

Sometimes we wait and wait to be accepted or approved by someone. But sometimes we need to do our homework, approve ourselves, and get it done.

The Secret to a Great Book Proposal

One of the things I noticed in my years as an acquisitions editor is that sometimes book proposals don't capture the personality and passion of the author. They are dry and sterile, and they don't really say much. Oftentimes, in-person meetings end up in book publishing deals easier than if only the book proposal is submitted.